Page 32: His eyes wandered back over towards the body of Aven, where the homes and stores and blacksmith shops and lumber yards nudged each other. It was built too tightly and he knew it. It didn't matter now, but the time would come when store fronts would have to be pushed back to widen the streets. "It's growin' crazy as a gourd vine flingin' out a creeper now and then and stores and houses hitchin' on whenever they feel like it."

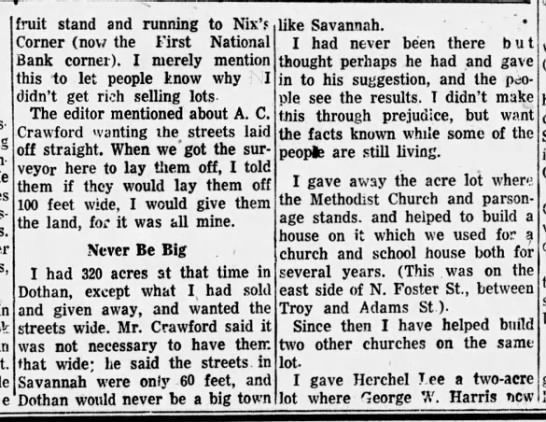

(from J.P. Folkes October 5, 1907 Letter to the Editor of the Dothan Eagle reprinted in the October 27, 1953 DOTHAN EAGLE)

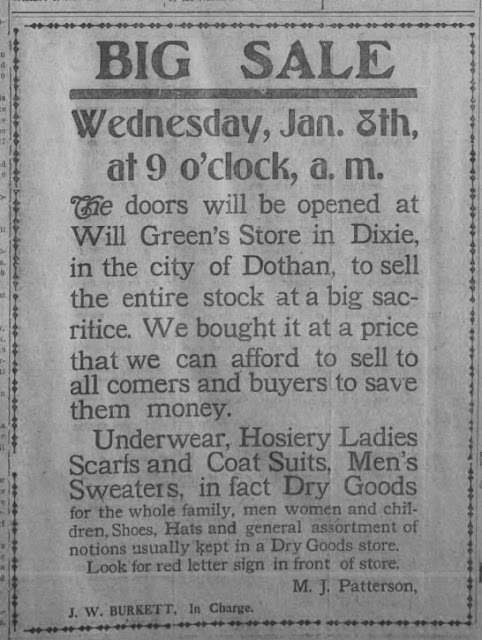

(from the January 9, 1898 MONTGOMERY ADVERTISER)

(from the August 15, 1929 Dothan Eagle)

from page 32: He

tightened his grip on the neck of the plain paper bag in his hand, and

held it closer against his leg, scowling uselessly as the small clump of

stores that had volunteered in the last year. "Half a mile from the

railroad," he thought, "just to get closer to the spring and the

distillery." He shook his head to clear it and started up the walk,

swinging his arms and hitting the gravel good solid licks with his

heels. "By God, business may leave where I am now, but it'll find me

where it's going when it gets there.

(from the April 16, 1931 DOTHAN EAGLE)

(from the August 18, 1899 COLUMBIA BREEZE)

from the August 15, 1929 DOTHAN EAGLE

from the September 23, 1933 DOTHAN EAGLE

from the December 3, 1950 DOTHAN EAGLE

page 33 of DEVIL MAKE A THIRD: Buck leaned closer to the opening, watching carefully, wondering if her hips swung free, trying to imagine what was going on under her full skirt. The hips had to swing free because her shoulders and head didn't move and she walked like a colored woman with a bundle on her head. He wondered and measured her in his mind. (A common sight in town like Aven would have been Black washerwomen walking down the street carrying bundles of laundry on their heads.)

from from the March 28, 1915 HOUSTON POST

Chapter 4

page 37 of DEVIL MAKE A THIRD: "...Buck was listening again to noises of the saloon. They came as if they were part of a crowded sleep. There was the jangle of the banjo, played day and night behind the thin partition that separated the whites from the colored folks' side. The banjo was supposed to have a happy whang to draw trade, but this time of night it was about played out. It was louder where Buck stood, near the curved slot through which the bartender shoved drinks to the Negro customers. There was the slow slap of cards on a damp table top, where three men played a careful hand of poker. There was always the steady thump-thump of a dog's hind foot scratching fleas under the bar." (from the November 28, 1935 DOTHAN EAGLE)

page 39: Even the sudden high-pitched yells from the Puddin' House were muted and sounded farther away than they really were. They always yelled in the Puddin' House. It was the only place for colored folks alone. A scuffle and a giggling laugh in the bushes near the narrow street came to Buck like an echo that had no beginning.

from the February 27, 1938 DOTHAN EAGLE: "There are not and never have been 'jouks' for Negroes in this section. The colored patrons, themselves, prefer the more descriptive definition of 'puddin' house. "

INTERLUDE #2- circa 1890 "He left in a rubber-tired buggy, all right." (pages 43-45)

"rubber-tired buggy"

By page 45 of DEVIL MAKE A THIRD, Buck Bannon has acquired a fashionable wardrobe, a new rubber-tired buggy and he's set his sights on marrying the richest man in Aven's daughter. (from the April 16, 1931 DOTHAN EAGLE)

from the March 7, 1931 DOTHAN EAGLE

from the January 13, 1920 Guntersville Advertiser

from the October 25, 1925 Montgomery Advertiser

from the April 25, 1955 Abilene Reporter-News

ROBERTOREG'S NOTES

SECTION 1

DEVIL MAKE A THIRD is not structurally complex. The events in each chapter occur chronologically from about 1890 until 1915; however, the author employs 12 asides called Interludes to move the timeline forward rapidly so that the novel can cover over 25 years of Buck Bannon's life within its 33 chapters. Each Interlude is a confidential conversation between two railway brakemen who always discuss the consequences of Buck's actions in Aven which have been described in a few previous chapters. Chapter 1, Chapter 2 and the first Interlude make up the first of these 13 major divisions of the novel. Chapter 1 and Chapter 2 describe Buck's life on the family farm, Buck's first impressions of Aven and how he got into the position to make his fortune on his first morning after waking up in town. The first Interlude has the brakemen discuss how the action in the first two chapters has shown how Buck became Aven's first teenage loan shark and on the road to riches a little over a year after arriving in town.

Chapter 1

Chapter

One introduces the reader to many important themes in the life of Buck Bannon which will be

repeated and will progress in subsequent chapters. Most important will

be the life-long burning desire of Buck to escape and to never return to rural life. Being raised with

"The Golden Rule" teachings of his Christian parents on their family

farm and facing the realities of Aven's materialistic boomtown society create a moral conflict which the novel will never resolve.

Buck will spend the rest of his life accumulating a fortune so he

could get as much money as he could put together between himself and his

family and a life dominated by child labor, debt peonage and

unrelenting, uncompensated toil. Buck's words and actions in the first

chapter create a foreshadowing of all the struggles Buck will face

during his unconventional career.

In

the opening scene of the novel DEVIL MAKE A THIRD, the reader is

introduced to young Buck Bannon behind his plow "blinded by the sun" with

sweat stinging his eyes and burning as it soaked into the raw places

on his neck chafed by his mule's reins but none of that mattered because

"he was eighteen and he was following a mule for the last

time." Popping a sweat in the early morning sunshine reminded Buck that

it was time for this "dirt road sport" to leave the farm and try his

luck in town. He had a twenty dollar gold coin burning a hole in his

pocket and the time had come for him to make his big move.

The label "dirt road sport" coming in the first paragraph of the second page of the novel holds much portent for this novel. The author's use of the word "sport" to describe his main character refers to the "sporting man culture" which is defined by Wikipedia as involving "men leading hedonistic lifestyles that included keeping mistresses as well as excessive eating, drinking, smoking, gambling, and big game hunting. It is applied to a large group of middle- and upper-class men in the mid-19th century, most often in Great Britain and the United States." The "dirt road" part of the label refers to Buck's isolated rural background. Once he leaves the family farm in Chapter 1 and in each subsequent chapter, the reader sees Buck adopt a Gulf South version of "sporting man culture" and after the first few chapters, only gains clues as to the precise methods used by Buck to quickly amass the great fortune necessary to support such a lifestyle and at the same time provide financial support to his 12 younger siblings.

To begin to build the better life required Buck to take his hard-earned $20 gold coin and to head to Aven, the new boomtown a few miles away from the Bannon farm. Suddenly rising out of the South Alabama piney-woods wilderness, the new town consisted of a railway station with a small row of

tin-roofed stores and unpainted houses.

Turning

his plow out of the soft dirt of the field, Buck looked between his

mule's ears for the last time to see his mother rocking on her porch as

he aimed his mule toward the sandy hard-packed clay of his Mama's

meticulously swept yard. Buck rejoiced at his coming freedom from the

drudgery of his parents' farm. In an act of both rebellion and celebration, Buck reined

his mule in concentric circles as he plowed up the bare-earth of his

Mama's front yard. Slapping his mule with the looped ends of his lines,

Buck yelled, danced and kicked up his heels while imitating the

movements of his mule. Finally, he calmed

down enough to speak and when he did, he imitated a square dance

caller,"ROUND AND ROUND, swing yore partner and do it again."

The

entire time he was plowing and rejoicing at his anticipated freedom,

Buck kept his eye on the second most important character in this novel:

his mother, Jeanie McPhearson Bannon, pregnant with her thirteenth child, who sat rocking on her front porch, dipping

snuff and observing her oldest boy showing off. After he finally

finished tearing up her carefully groomed yard and telling her he was

heading to Aven, Jeanie remarked, "Them pickpockets'll fight over you." Mrs. Bannon obviously had no confidence in her oldest son's ability to succeed in a town that was as far as she could tell nothing more than a den of thieves.

The

novel's second scene occurs inside the Bannon family home after the

evening meal with Buck preparing to get a ride to Aven that night with

his younger brother Jeff driving him to town in the Bannon's flat-bed

wagon. As Buck prepares to leave the farm for the last time, the

reader is introduced to two of Buck's brothers and his father Joe. The

other Bannon children are present but the reader only gets important

information describing Buck's younger brothers, Jeff and Hearn. These

five characters described in this first chapter (Buck Bannon, Mrs. Joe

Bannon, Joe Bannon, Jeff Bannon and Hearn Bannon) are the ones from

which most of the action in the novel grows.

One of the most important things that occurs in this first introduction of the entire Bannon family is the fuss created when Buck exclaims "For God's sake..." in reaction to one of his brothers. This use of the Lord's name in vain elicits a scolding from Buck's mother and gives the reader an indication of how far Buck is about to fall from his parent's expectations. The rest of the novel will reveal one example after another of how Buck's absolute lack of spiritual vitality provides him with no protection against succumbing to worldly Aven's carnal temptations.

The

novel's third scene describes Buck and Jeff's evening journey to Aven

and the reader gains insight into Buck's personality as the monotony of

the wagon ride produces a stream of images from his consciousness which

causes the young man to recollect scenes from the rural life he is

abandoning and producing the first feelings on homesickness.

Rather

than having Jeff cross a creek with his wagon, Buck jumps off the

wagon, bids goodbye to his little brother and walks the remaining half

mile into Aven. In the last paragraphs of Chapter 1, the reader is

finally told that the scene of the action in the novel will mostly occur

"in a small corner of Alabama [that] wasn't lying fallow any longer,

but was heavy with the germ of a town."

Chapter 1 ends with teenage Buck walking "into the moon and looking it in the face and he could almost feel it as he crossed the tracks." The reader still has no idea that young Buck is a commercial and political genius but here we see that Buck felt he had been touched by a higher power as he walked along Aven's tracks and sensed his fate and his future were in "Aven's first row of tin-roofed shacks." With his fourth-grade education, a few wagon rides to the grist mill and more than a few years experience in working his tail off for nothing other than for the privilege of being the oldest child and living on Mama and Daddy's farm, a hungry Buck walked toward Aven bursting with enthusiasm.

Filled with ambition, Buck left his family's farm with little idea of his future other than he "ain't aimin' to dig in no dirt." The new set of railroad tracks gleaming below his family farm were pointing toward a new life that promised to be better than the one he had before.

Chapter 1 also introduces Buck's attitude toward other major characters in the novel. As Buck plowed he noticed his mother rocking on her porch. He saw she had begun to show her age. Pregnant with her thirteenth child, Buck noticed his mother "was wearing the shapeless dress she always wore when she was going to have another baby." He also took note of "the first solid streaks of grey in her hair." Buck "shifted his eyes to his mother's face. It was swollen a little, around the jaw..." and he "could tell how she felt by the tired puffiness around her eyes." Mrs. Joe Bannon may have been dipping snuff to relieve a toothache and she was probably about ready to get some store-bought teeth and that took money. That was one more reason for Buck to head out for Aven immediately and to get rich quick.

The things about Buck's mother which draw his attention show he was fully aware at a young age of what a toll a life-time of grueling farm labor took upon a person entering middle-age. Throughout the novel, Buck continually exhibits this ability to get inside another person's head, to find out what they want and to give it to them.

On the second page of the novel a foreshadowing of the coming moral conflict between Buck and his parents comes when the author describes the "sense of power" Buck experiences as he plows up his mother's meticulously swept yard that has him "swingy in the hips like a dirt-road sport." The use of the term "dirt road sport" tells the reader that even though Buck's parents may have wanted Buck to follow the moral compass they provided for him in their home, the realities of winning the daily commercial battle on Aven's dusty streets would require some bending of "the Golden Rule." As Buck would ask his brother, Jeff, later in the novel, "Don't you know a man is bound to stir up some mud when he kicks off from bottom?"

Not only does Buck trust his younger brother Jeff to drive him to Aven on the family wagon but also felt "it's high time you'uz learnin' the way to Aven." Buck goes on to reassure his mother, "You'll all have to be comin' in town to see me, and Jeff can drive you." Buck's last words of warning to Jeff before walking into town shows Buck expects Jeff to take his place in the family, "Don't let Papa make you plow the big mule, boy. Big John'll pure pull yore arms out at the sockets. But you got to quit sleepin' in the cotton rows when you ought to be choppin'."

In the first chapter, eighteen year-old Buck takes every opportunity to speak dismissively about life on the family farm. When his father remarks about how much Buck resembles members of his mother's family, Buck jokes that his nose has a hump in it because "that comes o' rootin' for vittles in his here sorry clay." At that smart remark, both Bannon parents defend their agrarian lifestyle. Buck's father responds, "We made vittles out o' that clay, Buck. And you et 'em. Don't run the land down."

The toll that a life behind the plow takes on a man is described with Joe Bannon's manner of walking, "His shamble was a little stiff now, bringing the hunch back to his shoulders, as if he were still thrusting hard against a plow stock." Buck's excitement about his move to Aven comes from his commitment that life away from the farm will be easier for him as well as for his entire family. Buck firmly believes the Bannons might not live longer in Aven but they'll sure want to live longer than they would growing cotton year in and year out. No matter how much he or his parents enjoy the love, companionship or other rewards of their family farm or how much Buck might miss it during his lonely hours alone in Aven, the promise of a new life outside the farm fills Buck with excitement from the first page of Chapter 1 to the last, "Buck didn't know what it was, but he knew he was too full to hold it."

Chapter 2

Chapter

2 opens on Buck's first morning in Aven with him resting on top of a

baggage truck beside Aven's railroad depot. The strict order of the

chapters does not prevent the author from taking an excursion into the

past. The first three pages of Chapter 2 describe, through Buck's

dream-like stream of consciousness, his impressions of two of his

younger brothers and his parents. Buck judges his new bed on top of the

baggage truck to be superior to the pallet which he had shared with two

brothers on the floor of their parents' house during the nights before

arriving in Aven. This view of the two younger brothers through Buck's

mind's eye shows the reader the characteristics of Jeff Bannon which

will lead him to become Buck's life-long business partner and the flaws

of Hearn Bannon which will result in Buck finally telling his despicable

brother in Chapter 27, "I'd have killed any other man. You'll be lucky

to just walk out."

After

thoughts of his brothers fade, Buck then recalls a philosophical

expression his mother used to describe the fear she held for the future

of her family: "Shirt sleeves to shirt sleeves." This popular 19th

century expression was used to describe the phenomenon of one generation

of a family that overcame poverty by accumulating wealth having the

family's fortune destroyed by the poor decisions of future generations

who refuse to make the sacrifices necessary to maintain the family's

assets. Jeannie Bannon's doubts about her sons' ability to hold on to

what she and her husband Joe had accumulated during the tumultuous years during and

immediately after Reconstruction scares Buck and drives Buck's ambition making him

strive to show his mother that she has raised a farm boy who uses his

rural experience to conquer every obstacle that the growing young town

of Aven puts in front of him.

This

chapter introduces the reader to the newly constructed town of Aven

consisting of "a row of tin-roofed store buildings lining the street

nearest the railroad" and a few unpainted houses. At the end of some

trails leading off from the one business street could be found a few

painted houses owned by the village elite. Buck sees Aven's new buggies

and painted houses and knows he has to find a way so he can own a new

buggy and a new house . As the novel progresses, this "germ of a town"

grows along with Buck's business success and just as Buck appears to

adopt Aven as his home at first sight, the people of Aven will also

adopt Buck as one of their own and will extend the opportunity for him

to express his commercial and political genius in every chapter of the

novel that follows this one. Buck's obsession with guiding Aven's growth

is a major force in moving the novel's action forward but Buck's first

impression of the town is that "right now it looks like somebody just

flung it out there because they didn't have no use for it."

Buck's

dream-like stream of consciousness is interrupted by the yells of a

railroad clerk who ends up offering Buck a laborer's job as soon as he

wakes up. Buck declines saying,"Much obliged but I ain't aimin' to dig

in no more dirt." Buck bids the clerk goodbye and hops off the baggage

truck to begin his first walk down Aven's single business street. He's

hungry and he wants a job "long as it ain't handlin' a tool."

Buck's

short journey ends in front of a general store where he encounters a

family from the country who have come to town intent on trading a calf

for seed and tobacco. As Buck and the family wait for the owner of the

store to finish taking care of his customers, Buck decides he'll do the owner of the store

a favor and see if he can be of service to the waiting family himself.

This results in Buck trading a sack of seed, two plugs of tobacco and a

stick of licorice candy for the calf. Both Buck and the family are

pleased with the trade and the family leaves the store with the goods

and with Buck in possession of the calf.

When the store owner

finally gets the time to wait on Buck, he is enraged to find out that

Buck has taken such liberty with his merchandise but when Buck offers to

buy the calf in order to cover the cost of merchandise he traded to the

family, the owner declines the offer because he knows the calf is worth

twice as much as the goods Buck traded for it. Buck asks for a job and

the owner agrees and shakes on the deal before he and Buck ever discuss

salary.

Their salary negotiations result in Buck getting the money he wants plus the owner agrees to allow Buck to live in the

back of the store. Living in proximity to the source of one's cash flow

is a theme repeated for the rest of the novel. The new store's business

is so hectic that the owner understands he needs an employee like Buck

and allowing him to live in the back of the store frees him from having

to open up in the morning. During these negotiations, Buck takes the

liberty of eating a couple of the store's bananas so Chapter 2 ends with Buck accomplishing everything he

set out to do on his first morning in Aven,"Food comes first. Then I got

to get me a job-job where a man don't have to use a tool." And Buck does

it all without ever breaking his $20 gold piece.

INTERLUDE #1

An interlude is a literary device where the author breaks from the narrative to insert a story that somehow connects to the theme of the novel. Twelve times through DEVIL MAKE A THIRD, the author breaks the flow of the narrative to give the reader an intimate conversation between two railroad brakemen, Jake Willis and Bascom Wooten. This first interlude is concurrent with the plot but moves the action forward 16 months.

From their first conversation we learn that the past year has been a lucrative one for young Buck Bannon's after-hours loan business @ Green's Store. By charging 25 % interest per week on a $2 loan, Buck spends his time making Aven's citizens his loan customers instead of making them his friends. In the case of Jake and Bascom, both of their lives of debt peonage to Buck Bannon began the day they were broke before payday but wanted to go the whorehouse. By pawning their watches and borrowing two bucks from Buck so they could go see Aven's girls, each one of the pair, in the words of Tennessee Ernie Ford, "sold his soul to the company store"; "The company store" in this case being a nineteen-year-old entrepreneur who only wants his loan customers to ignore their mounting debt and to cover their loan's interest every payday, insuring that they live the rest of their lives making Buck Bannon a profit.

Both of these brakemen feel like idiots when they have to give this new kid in town money every payday but Bascom has the added guilt of knowing "I'm the damned fool that started it all. 'F I hadn't borrowed the first dollar from Buck Bannon, he'd never o' made a loan. I was itchin' to get to Mabe's place and didn't have a copper. By God, I had to tell him how much interest to charge, and I offered to put up my watch."

Buck Bannon missed out on attending a university's school of commerce so the dusty streets of Aven became his classroom and every railroad payday found him marking his account book, collecting his loan payments and "figurin' how much us railroaders own him. Been there ever' payday for over a year." Buck's successful first year living in town taught him many tricks of his new trade but he also learned to acquire some of same habits that afflicted his loan customers. Jake and Bascom took satisfaction in knowing that they were there when Buck, the green country boy who just walked out of the piney woods, was introduced to Aven's sketchy adult entertainment provided by the whores down at Mabe's Place. As they laugh about the memory, Jake imitates Buck's slow drawl as he stood goggling the elaborate curtains and mirrors inside the fancy foyer of Mabe's place, "Jake, them's white girls."

With this first mention of the race of Mabe's prostitutes, the author lets the reader know that Aven is a segregated society and during the course of the novel, the author never makes comments nor condemns Aven's discriminatory customs which condemned many of its residents to a life of toil for which they received little compensation. There are no strong Black characters in the novel and in the twenty or so places where Blacks make an appearance, they work in menial jobs such as waiters, bellboys, cooks, shoe shine boys, maids, cooks, chauffeurs, or farm laborers. The closest the author gets to an enterprising Black character is a street corner preacher who has some goats to sell. The legacy of slavery is mentioned only once and that is part of an elaborate rationalization concerning his rich former father-in-law which Buck creates to justify his own greed, "I got no guilty feelings. Maybe I've squeezed a mortgage too close and maybe I've shaved off a little for myself when I bought for the city. Folks forget anyhow. They've forgot how old Longshore's folks trafficked in slaves so they could raise him in a big white house in the middle of ten thousand acres of sandy loam. Maybe forty-fifty years from now, some Bannon'll be oozin' religion at the church door and folks won't remember that Buck turned his eyes off while his hands gathered a crop they didn't make."

In these first two chapters and the interlude, Dougie Bailey establishes most of the characters from which all of the novel's action will emerge and gives the reader a vivid portrait of a railroad boomtown's commercial environment which produces all of the obstacles that the character of Buck Bannon will conquer. There's no idealism or striving for social justice in Devil Make A Third. It is a down-to-earth story of how one country boy leaves home to move to a strange place armed only with a $20 gold coin and an optimism which allows him to confront everything that stands in the way of his progress and to overcome every challenge.

Chapter 3

Chapter 3 begins the next segment of the book sixteen months after Buck's arrival in boomtown Aven. Aven hadn't progressed to the point of actually having a bank so negotiations for Buck's first business loan would occur on the front porch of Amos Longshore's big house. While working up the courage to ask the richest man in town for a loan, Buck reflected upon his new life as he stood on the street in front of the Longshore's house. Aven had grown from a row of wooden shacks across from a railroad depot. Fresh water from a spring a half mile away from the depot had led to the construction of a whiskey distillery and with it a new commercial district emerged to compete with the one by the depot where Buck worked.

The hick from the sticks who'd never even seen a train a few months before now recognized each engineer's whistle and pawning those railroad men's pocket watches was the new crop country boy Buck was tending now. Harvest time was every railroad man's payday and Buck knew he was on the path to riches because he's "willin' to live like a hog in the back of Green's store, and stayin' lonesome because you can't make money by lendin' to friends."

Buck's short loan business was only part of his commercial education in Aven. Months of serving Aven's public at the counter of Green's store had honed Buck's powers of persuasion and convinced him that he'd found a way to make money so he could get ahead in the world but "getting ahead" for Buck meant more than just becoming a well-to-do counter clerk. Buck wanted to be lead wolf in the pack that ran the town. Buck's exaggerated individualism in Aven's developing urban environment was forged on a cotton farm where each day had seen the Bannon family struggle for existence.

Longshore's daughter answered Buck's knock at the front door and this resulted in Buck discovering he wanted a little more from Longshore than just his money. As he watched the pretty girl walk down the hall to go get her father, Buck craved what he saw, "like finding rock candy in the syrup bucket."

Suddenly, Buck had more than business on his mind. The brown paper bag in which Buck carried the down payment for the mortgage he was seeking, along with his well-worn wardrobe, had not enhanced Buck's first impression upon Longshore and seeing Buck's interest in his daughter didn't help Buck's chances of getting a loan.

Buck overcame all of Longshore's suspicions simply by allowing the old man to have a glimpse of the inside of the paper sack filled with Buck's greenbacks. When Longshore pointed out that he could easily use his own money to buy the bargain-priced property Buck desired rather than financing Buck's purchase, Buck pointed out that Longshore would rather have Buck's five hundred dollars than a bargain price on the property and Buck was correct. When Buck told the old man, "You want my five hundred," Longshore responded, "You're right and I think I'm going to get it. Come back tomorrow and I'll have the money and the papers ready."

After knocking on Longshore's front door, Buck discovers the existence of Longshore's daughter. Suddenly, Buck has more than business on his mind. The brown paper bag in which Buck carried the down payment for the mortgage he was seeking along with his well-worn wardrobe had not enhanced Buck's first impression upon Longshore but seeing Buck's interest in his daughter didn't help Buck's chances of getting a loan. Buck overcomes all of Longshore's suspicions simply by allowing the old man to have a glimpse of the inside of the paper sack filled with Buck's greenbacks. When Longshore points out that he could easily use his own money to buy the bargain-priced property Buck desires rather than financing Buck's purchase, Buck points out that Longshore would rather have Buck's five hundred dollars than a bargain price on the property and Buck was correct. Even though the two part with Longshore insulting Buck by calling him a thief for exploiting a tragedy, Buck walks off Longshore's porch and into Aven's night knowing that his business plan has made a tremendous leap forward. Buck's last words to Longshore give a good description of Buck's strategy, "I ain't got time to stop and build bridges when I come to a creek. I've got to jump to stay on schedule."

Even though Longshore insulted Buck by calling him a thief for exploiting a tragedy, Buck walks off Longshore's porch and into Aven's night confident that his business plan had made a tremendous leap forward. Buck's last words to Longshore give a good description of Buck's strategy, "I ain't got time to stop and build bridges when I come to a creek. I've got to jump to stay on schedule."

CHAPTER 4

Chapter

4 opens with Buck finishing off a glass of whiskey in Aven's only

saloon, a "Jim Crow" enterprise with a double ended pine bar that

separated the races by means of a thin partition across the middle of

the bar and serving its Black customers through a curved slot cut into

the flimsy wall which allowed the banjo music from their end of the bar

to entertain the saloon's entire crowd.

No

matter how intelligent 20 year-old Buck might have been, Aven's corn

liquor was guaranteed to help him do something stupid so he had sense

enough before beginning his drunken evening to deposit in the saloon's

safe the $500 down payment he'd taken to Longshore's house for the

mortgage negotiation. As the bartender pours Buck one more for the road,

he reminds Buck of how liquor stirs evil passions by paraphrasing a

proverb from the Bible, "It stingeth like an adder and biteth like a

serpent." This biblical reference may not be the only one in this

chapter.

Buck

had a lot on his mind. Not only was he going to close on his first

mortgage the next day but he was now sitting on a bar stool lost in lust

while his mind's eye attempted to recall every detail of Longshore's

gorgeous daughter. There was no way Buck was going to accomplish

anything listening to the saloon's banjo music and dreaming about the

blonde-headed eye candy he'd just left at Longshore's house. Buck's

barroom boredom could easily be eliminated with only a short walk from

the saloon through Baptist Bottom to the place where Buck's payday loan

customers spent the money they borrowed from him: Mabe's whorehouse.

Buck's customers were also the customers of Mabe's girls and on this

night Buck decided to get stupid just like the rest of them and to seek

satisfaction in the arms of one of Aven's lewd women. As Buck told the

bartender before he left the saloon, " I'm a'goin' to Mabe's Place and

kiss all the girls and run climb a tree an' wait for them to cut me

down."

Like

the moon on that night when Buck first walked into Aven sixteen months

earlier, the moonlight on this foggy evening filled liquored-up Buck

with a sense of the potential power he'd discovered which assured him

that he would one day achieve his destiny and make a fortune from Aven's

populace but the corn liquor he'd consumed guaranteed that this late

night stroll was not going to contribute to his future fortune. Like the

maxim "nothing good ever happens after midnight", Buck's evening ramble

to Mabe's Place would never fulfill the promises the moonlight was

making.

As

he walked through muddy Baptist Bottom, a stumbling, drunken Buck

encountered a street corner preacher who was just ending the sermon he

was preaching to a crowd gathered on the street in front of a honky tonk

called the Puddin' House. Buck immediately requests that the reverend

"Preach me some hell-fire and alligator teeth."

The

Black preacher, an experienced salesman, immediately sizes Buck up and

begins a series of questions, each one ending with the preacher calling

Buck, apparently a total stranger, the "boss." By calling Buck "boss",

the preacher was going through all the motions that showed him to be a

"good, humble Negro" while at the same time setting Buck up to purchase

"a pair o' fine billy goats, Boss, which'd make mighty pretty pets" for

the whores Buck was about to meet at the brothel just beyond Baptist

Bottom.

Possibly

as an allusion to the bizarre biblical story in Genesis of Judah

promising to pay for the services of the Bible's first prostitute with a

goat, the author of DEVIL MAKE A THIRD has his protagonist tugging a pair of billy goats into an elaborately decorated den of iniquity.

Taking goats inside a whorehouse is a prescription for disaster and the

destruction the charging goats' horns made of the bordello's mirrors

and vases ends this chapter with the brothel owner telling Buck, "Even a

whore has got feelin's and if a fellow can't earn the name of a

gentleman in a whorehouse, he won't get it nowhere."

Stung

by the insult, Buck sobers up a little and makes a prophetic statement

on this night before he was to sign his first mortgage with Longshore ,

"There'll be a man out here tomorrow mornin' to fix your place back. I

don't give a damn about bein' a gentleman, but, by God, I'll be payin'

my debts, till I die."

No

doubt that the man who would show up the next morning to repair Buck's

damage to Mabe's Place would also be one of his payday loan customers

who was trying to settle up some of his debt by doing day labor for

Buck. Buck's

repair job and his replacement of the broken furniture also had him

investing in Mabe's lucrative sex-trade business and subsequent events

would show that Buck's attempt to make right his senseless destruction

would enhance his reputation with Mabe as well as with the girls who

worked for him. Buck's drunken stunt would enable the young

entrepreneur to seamlessly transition into a more vertically integrated

business plan.

INTERLUDE #2

Each of the novel's 12 INTERLUDES moves the novel's plot forward in time. In the case of INTERLUDE #2, the action occurs four months after Buck's visit to Mabe's Place the night he struck a deal with Longshore for the mortgage that enabled him to buy Green's store. Twenty year-old Buck is now two years along in his successful business career.

The tragicomedy quality of Buck's billy goats' visit to Mabe's Place in Chapter 4 continues in INTERLUDE #2 as the story opens with Jake's arrival at the Aven freight depot aboard the No. 54 train from Albany. Jake is so hungover that simply walking is painful for him and not only that, he's broke and late paying on his loan from Buck. Jake meets his fellow brakeman, Bass, who brings more bad news by informing Jake that his watch is gone because Buck has left town. Jake tries to process this information and exclaims, "Wheeoo, watch gone, job gone."

Jake's sad conclusion, causes Bass to show his railroading friend some sympathy and to reassure Jake that all is not lost and that Buck will soon return from his short trip back home. This news lifts Jake's spirits momentarily but as he contemplates the future of his watch, Jake says, "I don't like this. He'll lose it, or break it, or, by God, he'll swap it off for a rubber-tired buggy."

Again Bass reassures Jake that Buck simply has gone back home to convince his parents to leave farm life and to move the entire family to Aven. This information only worsens Jake's bleak attitude because he knows that the demands of Buck's family will mean that Buck will become an even greedier pawnbroker and payday loan shark.

INTERLUDE #2 ends with Bass finally agreeing with Jake's conclusion that the future of Jake's watch, as well as his brakeman job, were indeed rather gloomy simply because Buck "left in a rubber-tired buggy, all right."

In each of their conversations, Jake and Bass discuss their grievances with Buck but they also discuss how Buck gives back to the same people he exploits. In the case of Jake, a hopeless victim of Buck's usurious lending practices, the years that this failed railroad brakeman spends working off his debt to Buck may give him status in the Aven community by Jake being one of "Buck's men" and of having the reputation of being commercially associated with Aven's most important decision maker, Buck Bannon.

The characters of Jake and Bass only appear in the novel's 12 Interludes and the progress of their lives and relationship gives the reader another window into the intimate details of Buck's life. Both of these undisciplined railroad brakemen allow their appetite for liquor and fast women to sink them into debt to Buck with no hope of recovery. The consequences of Buck's financial robbery are quite severe for Jake. INTERLUDE #2 will be the last time the reader will see Jake on a train. For the rest of the novel, Jake will never return to railroading and he will spend the rest of his time working odd jobs for Buck in order to pay off his debt. This form of debt slavery doesn't totally annihilate Jake's autonomy, however, his financial bondage to Buck will limit Jake's options and his only escape from continual debt would to be to move out of Aven and to run away.

The last line of INTERLUDE #2, "He left town in a rubber-tired buggy, all right,"also gives us insight into Buck's motivation. One of the first things that impressed Buck during his first morning in Aven was "a small neat buggy with new harness." That Buck chose to visit his parents' farm in a "rubber-tired buggy" shows that Buck is adapting to life in Aven by acquiring all of the status symbols associated with his small town business success.

Chapter 5

The events described in Chapter 5 take place where most of the events of Chapter 1 took place, on the Bannon farm a few miles outside Aven. In fact, Chapter 5 reintroduces all of the characters the reader encountered in Chapter 1: Joe Bannon, Jeanie Bannon and two of Buck's younger brothers, Hearn and Jeff. Buck's return to the Bannon farm takes place about 1889, two years after Buck made the decision to move to Aven when he turned 18. Times have changed on the Bannon farm. Even though Joe Bannon is still a prosperous farmer, time and hard labor have taken its toll on old man Bannon and as he loses his strength the Bannon farm risks falling apart because when it comes to Buck's younger brothers "ain't neither one of them too much hand to work."

Chapter 5 opens with Buck loosening the reins on his little red mare so he can speed his shiny new rubber-tired buggy down the road toward the Bannon family farm. He's wearing a derby hat and dressed in his Sunday best coat and tie but protected from the road dust by a driving coat. 20 year-old Buck has now acquired all the hallmarks of a successful businessman but it's hard to imagine that a former farm boy who'd never left home during his first eighteen years of life would move to a town only a few hours wagon ride away from his childhood home and then wait two years before returning to visit his parents and twelve brothers and sisters at the old home place but once the reader understands the purpose of Buck's mission, his absence begins to make sense. Buck hasn't visited his parents in two years because Buck was too busy making money and now he plans on using that money to create a better life for his large family. Buck senses that the new growing season will be his father's last cotton crop but Buck believes he has a way for his father to avoid the grave, to cease his hard labor and to enjoy his last days by leaving the Bannon farm and moving to Aven. Buck feels he can successfully convince his parents to make such a drastic change because he's now made enough money in Aven to make it happen.

It had been four months since Buck closed the deal to buy Green's store in Aven and by this time, he'd accumulated enough cash from that enterprise along with his payday loan business to accomplish his mission which according to Bascom in Interlude #2 was "to argy his folks into movin' to Aven." There will be one person in the Bannon family who Buck won't have to convince to move and that's his brother Hearn who, upon Buck's arrival at the Bannon place, sees Buck's latest fashion and brand-new rig and exclaims, "Look here, Buck. Take me back when you go. Maybe I can get a buggy, too." Convincing Buck parents to leave the family farm and move to Aven was going to be a lot more challenging than convincing his little brother.

Buck had taken on a great challenge when he decided that after a two year absence, he would return to the Bannon farm and reframe reality for his family by convincing his parents to leave their farm. If experience is the measure of a life then the commercial life of a railroad town beats the Bannon farm every time but if the measure of one's life is love and companionship, then the family farm beats the Aven rat race every time. Buck understands this as he approaches the Bannon place in his new rubber-tired buggy. He reminisces about the smells and tastes of his childhood, saying to himself, "Hey, Lord, a little eatin' like that will make me forget the grubbin' I been doin'. Sellin' and buyin' all day and lendin' and collectin' most of the night. Worth it, though, ever' minute of it." In Chapter 1, Buck let his parents know what he thought of their farm when he joked that the hump in his nose "comes o' rootin' for vittles in this here sorry clay." Now in Chapter 5, Buck has sharpened his argument when he tells his father, "Farmin' right now ain't helpin' you none." To his Mother, Buck is even more brutal in his opinion of the Bannon farm's future, "Sell it, or throw it away. Do anything, but get Papa off it."

One of Jeanie Bannon's favorite expressions is, "Shirtsleaves to shirtsleaves." This 19th century maxim refers to the tendency of the children of those who have escaped poverty to squander what wealth their parents have accumulated and to see the family return to a state of poverty. Buck shares the same fear as his mother and his attempt to create his own commercial empire in Aven is his way to avoid catastrophe because Buck knows that he will never take his father's place on the family farm and he also knows his brothers will never succeed at farming. As he tells his mother, "...they won't never put out enough on this place to help Pa much. This ain't no one horse farm. It needs good labor and lots of it."

Buck has an alternative to farming. Buck proposes that the family move to Aven so they can "farm" the farmer. Buck asserts to his mother,"Look, pore farmers have got to be furnished and somebody's got to furnish them...See here, the man that does the furnishin' makes more'n the farmer. You know that. Rent him his land, sell him his tools, seeds, guano, anything he wants. He'll owe you and he won't like you. He'll cuss you, but you'll have to take it. He may kick you, but take it. Then, by God, if he makes a crop, take it."

Aven's dishonest commercial world which Buck describes to his mother abounds with every social evil associated with greed gratification but Buck's argument makes an impression on Jeanie Bannon. She knows that the farm's future is unsustainable. As she tells Buck, "A man breaks land for forty years but the land don't break a man but once." But Aven's ways aren't the Bannon ways and Mrs. Bannon cannot imagine selling her family's hard earned land and moving to a town where "them pickpockets'll fight over you." Buck ends his sales pitch to his mother before it turns into an argument by saying, "You all muddle it out tonight. It won't hurt." With that mother and son call it a night and go to bed.

From his pallet on the floor in the children's room, Buck finds himself unable to sleep. Laying there, Buck listens to the sounds coming from his parents' room. When he hears his mother get out of bed and walk into the kitchen to the back porch, Buck gets up and follows her outside and whispers, wanting to know what his father said about moving to Aven. His mother replies, "What did he say? What he said don't count. It's other things. It was him- fumblin' at the ham tonight, and hackin' it up when he used to cut it like butter. It's me havin' to button his shirt and make out like I'm doin' it for fun. It's them things, them, and him turnin' over in yonder and flingin' his poor stiff hands out in his sleep. They're the things that'll move us."

Buck knows that his mother is the decision maker in the family and that this is one decision that she doesn't want to have to make. Buck leaves his mother on the back porch but before closing the door, he overhears her prayer which she whispers as she stands on the porch looking up to the heavens, "Please don't let me be scared of all them folks."

Mrs. Bannon understands that there is no alternative to leaving the farm so the family will move to Aven but she will never forget the cotton farm. She and her family's memories of the good things about farm life will become an Edenic myth. In modern Aven the Bannons will preserve many of their rural customs and continue to eat their country cooking as reminders of the happier and more harmonious life they lived but lost when they left the farm.

INTERLUDE #3

The third section of DEVIL MAKE A THIRD consists of only Chapter 5 and Interlude #3. By showing the circumstances under which the Bannons leave their farm, this short section sets the stage for the rest of the novel. In Chapter 5, Buck convinces his aging parents that their failing health guarantees that their cotton farm is an unsustainable enterprise and that an alternative and profitable form of commerce may be found in Aven because that's the place where the area's poor farmers go to borrow money each year to finance their next season's crop and when that crop is harvested, those same poor farmers must surrender their harvested crops to their lender or turn over all property which was used as their collateral for their initial loan. Buck's mother is repelled by Buck's description of such a way of making a living but Buck wins the argument simply by saying, "Them that furnishes live a long time. The land don't break them."

The Bannon's farmland had certainly broken Buck's father, Joe Bannon, and Buck's mother knows it. Since she is the decision maker in the Bannon family, she makes the choice to leave her old way of life for the modern conveniences of Aven's emerging industrial urban society. She summons all her faith in preparation for this radical change and sends up a simple prayer to her Lord, "Please don't let me be scared of all them folks."

One of "all them folks" in Aven is a former railroad brakeman named Jake Willis. The reader only sees Jake in the novel's interludes which are a literary device which the author uses to advance the novel's time line. Interlude #3 opens with a miserable Jake Willis talking to himself as he stares into the flames of the fire he has built with the scrap wood left over from the construction of the big house Buck Bannon is building for his family in Aven. "Bible says we'll always have pore folks. But how come, by God, it's got to be me?"

Jake lost his watch and his job in Interlude #2 so now he's doing odd jobs for his lender, Buck Bannon. Buck convinced his mother and father to move the family to Aven and now he is constructing them a house big enough to serve the large Bannon family. Buck has hired Jake to be his nightwatchman.

Jake's friend, Bascom Wooten, overhears Jake's complaints and joins him at his fire. Bascom checks the time on his watch and remarks that it is past midnight. Seeing Bascom look at his timepiece irritates Jake even more because it reminds Jake of his own railroad watch which he lost to Buck due to a late payment. Without his watch, Jake lost his job as a brakeman. Jake continues to gripe to Bascom, "Be damned if they ain't somethin' wrong when a man can lend you two dollars on a sixty-dollar watch, then in two-three year have it run up to more'n the watch cost."

When you owe money, you don't own yourself. You may not be in a condition of actual slavery but your "chains" are disguised under a form of contract labor and peonage or debt slavery. Your lender has a mortgage on you. This is the tough lesson that Jake Willis finally learns in Interlude #3. In the first two interludes, Jake is working as a brakeman on the railroad but a late payment on Jake's payday loan caused his creditor, Buck Bannon, to foreclose on Jake's railroad watch and as Jake says in Interlude #2, "Wheeoo, watch gone, job gone." In the novel's final eight interludes, Jake never returns to his railroad job and lives the rest of his working life doing odd jobs for Buck or for one of Buck's political cronies. Toward the end of the novel, Buck gives Jake his watch back but Jake's too old to go back to work on the railroad. As a consequence of a single payday loan, Jake Willis spends his entire working life as Buck Bannon's "mule." As Jake says in the novel's last interlude, "Me, I'm a damned mule. I just drag along, gee or haw."

ROBERTREG'S CRITICAL COMMENTARY on SECTION 4 & CHAPTER 6

Section 4 of DEVIL MAKE A THIRD is made up of Chapter 6, Chapter 7 and Interlude #4. This section describes the Bannon family move to Aven, Buck's scandalous relationship with Big Vic and Buck's leadership in laying out the street plan for the town of Aven. It's about August of 1890 so Buck is only 21 years old but in the three years since leaving home, Buck's general store and payday loan business in Aven have already made him a wealthy young man.

One of the most important literary achievements of the novel DEVIL MAKE A THIRD is the synthesis of the maturation of a man named Buck Bannon with the simultaneous development of the railroad boom town of Aven. The time and place of this 30 year-long saga of American enterprise are a potential point of confusion for the reader because the first date mentioned in the book comes on page 215 and in the first 58 pages, the only clue as to the geographical location of Aven is that it is located in "a small corner of Alabama" that's probably a day's train ride away from Albany, Georgia. The author's avoidance of a narrow identification of his fictional places and characters may have been his attempt to have the reader view the events of the novel as events that could have occurred anywhere in which similar conditions prevailed and that the people portrayed in the book could exist wherever human beings live.

Any confusion produced by this intentional ambiguity fades away when one understands that the present-day city of Dothan, Alabama is called "Aven" in the novel. Anyone familiar with Dothan's people, history and geography has no problem understanding where the author found inspiration for the creation of his fictional place and characters. A literary critic in the September 12, 1948 ATLANTA CONSTITUTION stated it well when he wrote, "DEVIL MAKE A THIRD rings true as an exciting portrait of a strong man and a bustling town. Perhaps it is more so because of the author's peculiar qualifications. For Dougie Bailey is a native of Dothan, the locale of his novel, and also comes from a family of strong men, any one of whom might have served as a pattern for Buck Bannon."

Chapter 6 opens with Buck daydreaming while leaning up against a tree located across St. Simon Street from the big unpainted house he just finished building for his family to move into when they roll into town on their wagons later that afternoon. Buck served as architect, building materials supplier, construction supervisor and interior decorator for this project and he's justly proud of his accomplishment because the location of the Aven city block of land he bought to build it on was across the street from his store so he was able to work on the house without it interfering with business at his store. Buck tells himself,"A man oughtn't to live over two hoe handles from his business."

Buck's life on the streets of Aven never changes the rural aphorisms that pepper his thoughts and his speech. "A hoe handle away" or "half a hoe handle away" was an expression familiar to most 19th-century American rural folk coast-to-coast to indicate close proximity. For the rest of the novel, the contrast between "life in the country" and "life in Aven" will be highlighted by the Aven residents preferring their rural vocabulary and table fare to whatever current food and fashion that's being offered by their newly founded railroad town. Eighteen chapters later in the novel, this preference for "all things rural" by early Aven residents begins to drive the novel's action after Buck's mother receives notice that she has a terminal case of cancer.

Buck's innocent daydream about his family's future in the big house he's built for them is interrupted by a question asked by a curious member of Aven's business community, an old mule trader. He asked, "Plannin' to fill it up someday?" Buck assures the old fellow that the house will certainly be filled but the children will be his brothers and sisters. Buck's success in town brought him to the attention of Aven's commercial interests and Buck's future prosperity will be insured by these commercial and political ties.

When the Bannon family arrives at their new home, Joe Bannon is more impressed with the soil of his house lot than he is with the house Buck built for him. He tells Buck,"Somethin' ought to grow there," pleased with Aven land's potential for gardening. Mr. Bannon goes on to tell Buck about the next crop that would be harvested on the land they just sold before moving to Aven, "Boy, you ain't never seen nothin' like the way that land was yeastin' when we sold. I figure the crop to come was what got us the price." Buck replies, "It was pretty good dirt." This comment is significant because it's the first time in the novel where Buck ever complimented the Bannon farm.

ROBERTOREG'S NOTES DEVIL MAKE A THIRD includes many descriptions of neighborhood landscaping in Aven (fictional town modeled on Dothan).

#1.

from page 31 (Buck is about to make his first big business deal with

his future father-in-law) He closed his lips tightly, remembering, and

trying not to remember, as he faced around to the big white house up the

precise gravel walkway that parted two squares of green lawn. "No time

to drag around,' he muttered, and took two steps again, staring in a

puzzled frown at the lawn. "More and more folks here lettin' grass grow

in their yards." He shrugged slightly. "Mother wouldn't have it."

#2.

from page 188-189 (circa 1906 description of the 1897 standpipe

reservoir still standing across from the depot in Dixie) They walked in

silence for a moment, Buck looking from bottom to top and then back down

along the tall straight-up-and-down standpipe reservoir. It still shone

with newness and the small triangular plot of ground was bare again

although it had been sodded with St. Augustine grass.

"Ain't as bulky as New York's," Buck said abruptly, "but man for man it'll hold as much as any in the world."

#3. from page 326: She would have had the sanded yard swept until nothing showed but the

short slanting scratches that followed the stroke of a homemade yard

broom.

#4. from page 335: His eyes had seen it for years, rain-washed and rutted, so that hardly a

stalk of dog fennel would fight its way up though old buggy axles, tin

cans, jars and bottles half full of brackish water, and his mind had

only said, "That lot ought to be cleaned up."

#5. from page 347: They saw instead the slow picture of high-piled cotton wagons grinding

slowly down limbs whose weight dragged them down into tired arcs. And

they saw the now even alignment of the homes on each side of the streets

as new builders took sight of their neighbors' fronts before they laid

foundations for their own. And the flowers- azaleas blazing a dusty

reddish orange against the white of a low fence, forsynthia hedges

throwing bright yellow bells up in challenge to the sun, Cape jessamine

shrubs dotting green lawns and mellowing the night, a pansy-bordered

walkway dancing with velvet browns and purples and yellows, dogwood

trees and redbuds teasing with white and pink petals the salty southwest

wind.

"Hey, Lord, they're puttin. silk stockin's on a reg'lar whore of a town."

#6. from page 369: "This town has meant a lot to me- it's been my friend and it's been my

good companion. It's given me more than a man deserves, and in giving

it, it's come a long way. All the way from a cold-water spring in a

grove of poplars to paved streets and a power plant. It's come to fine

homes and flowers brought in from Mobile- azaleas to bring something

besides work to all of us. I hope this opera house will do the same

thing the flowers did for us- make us forget for a while that we're

building a town and then remember stronger that we are growing with it,

and be thankful to the town. I'm grateful to Aven because it took me

along for the ride."

#7. [not pertaining to residential

landscaping but to suburban Dothan] from page 197: "Give me a shot

quick," he said, "I think I swallowed some of that rain."

"Phew!" he said, looking back up at Buck. "I can't do worth a cuss with

her. Jeff, he can sit still and look picked on and get what he wants. It

looked like I kept her riled up so I came on down."

"Shirt sleeves to shirt sleeves," Hearn said, suddenly, without smiling. "That's what she kept saying."

His mind suddenly was back to the first night he had spent in Aven, a

night when the fear had found him alone. That fear- part of the fight

between man and cotton, or man and land, or man and grass. Bermuda

grass, lacing a foot deep into the richest soil, holding it against the

heavy washing rains and fattening the topsoil for the day when a man

would need it. Bermuda grass, friendly at first, then a part of the

fight, dirt banker for the man, then making him earn it, making him go

in there with a steel beam and a bull-tongue scooter and a mule that was

willing to burn itself out alongside of a man. He shuddered, then

looked back up at Hearn.

"Shirtsleeves," he said, softly,"in three generations."

"She says it looks like we're fixin' to do it in one."